Quality is key

Authors: Esther Plomp & Antonio Schettino & Emmy Tsang

The quality of research is important to advance our knowledge in any field. To evaluate this quality is a complicated task, since there is no agreement in the research community on what high-quality research is, and no objective set of criteria to really quantify the quality of science.

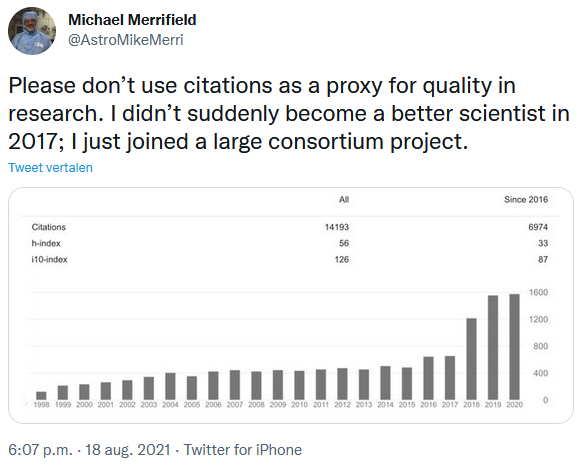

Where some try to argue that quantitative metrics, such as the ‘journal impact factor’ and the ‘h-index’ are objective measurements of research quality, there is plenty of scientific literature that provides evidence for the exact opposite. This blog delves into some of that literature and questions the objectivity of these metrics.

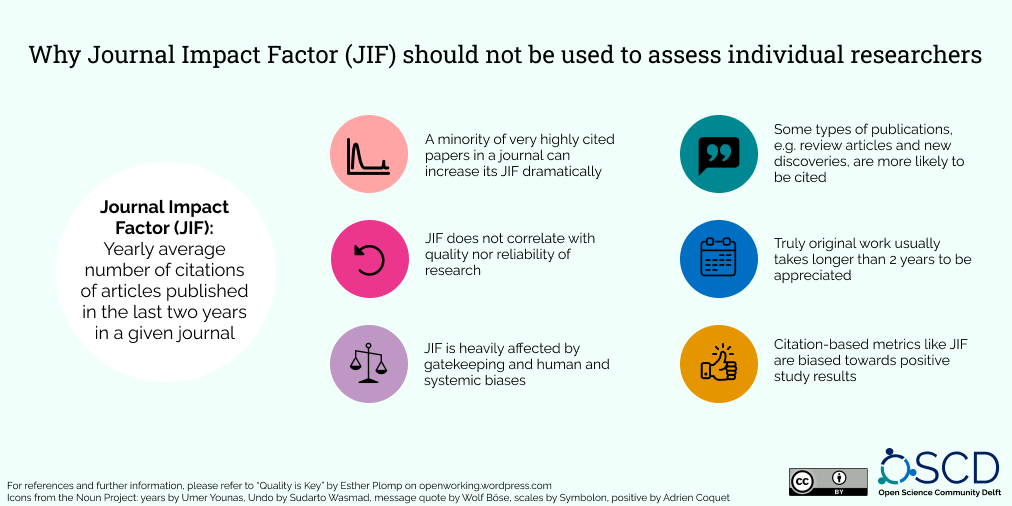

Journal Impact factor

The Journal Impact Factor (JIF) was originally established to help librarians identify the most influential journals based on the number of citations the journal’s publications have received over the two preceding years. If this was the intended purpose, why is the JIF currently embraced as an indicator of the importance of a single publication within that journal? Or even further removed, used to assess the quality of the work by individual scientists?

Multiple studies demonstrated concerns regarding the use of the Journal Impact Factor for research assessment as the numbers, to put it bluntly, do not add up:

- The citation frequency of the journal does not predict the citation frequency for its individual articles.1 Increasingly highly cited papers are coming from journals with a lower JIF.

- Rather, there seems to be no correlation between the quality or reliability of research and the Journal Impact Factor, with retractions, data falsification and errors more often found in high-impact journals. See ‘Prestigious Science Journals Struggle to Reach Even Average Reliability’ for a more extensive discussion and references.

- The Journal Impact Factor may say nothing about the true value of the research to a field, especially seeing that review articles and new discoveries are disproportionately cited. The impact of novel findings takes longer than the two years on which the Journal Impact Factor is established. By focusing on the impact factor the importance of non-ground-breaking work is undermined.

- By focusing on the mean, rather than the median, the JIF is also arbitrarily increased by 30-50%. Journals with high ratings appear to depend on a minority of very highly cited papers, overestimating the real citation rate.

As if that isn’t enough, the journal impact factor is also heavily affected by gatekeeping and human biases. Citation metrics reflect biases and exclusionary networks that systemically disadvantage women2 and the global majority (see for example racial disparities in grant funding from the NIH). Citations themselves are also biased towards positive outcomes. Reviewers and editors have also tried to increase their citations by requesting references to their work in the peer review process. Authors themselves can also decide to needlessly cite their own papers, or set up agreements with others to cite each other’s papers and thus artificially increase citations.

Commercial interests

Next to the inaccuracies and biases in using the JIF for quality assessment, it should be noted that the JIF is a commercial product managed by a private company: Clarivate Analytics. This raises further points of concern as the missions of commercial companies do not necessarily align with those of universities.

- The JIF is negotiable as journals can discuss which types of articles to include and thereby artificially increase the impact factor. These processes make it also impossible to reproduce the values of the JIF.

- Publishing in prestige journals has resulted in exorbitant prices for open access publishing, which excludes anyone that does not have funding for this to participate in the research assessment game.

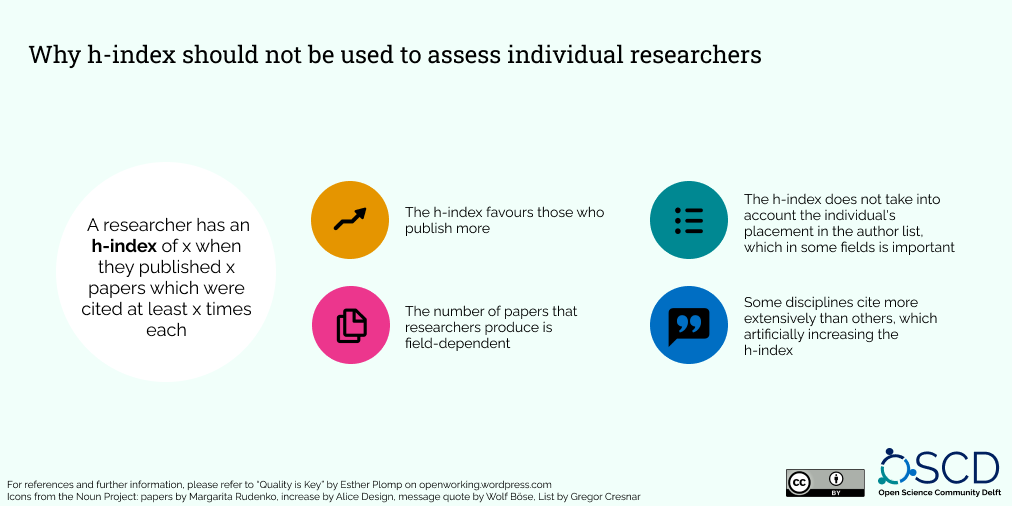

h-index

The h-index is another metric that tracks citations. A researcher has an h-index of x when they published x papers which were cited at least x times each. While this metric was developed to assess productivity and research impact at the individual level, it is routinely used for research assessment. This is problematic, as it is based on the same underlying issues of other citation-based metrics (as described above). Furthermore:

- The number of papers that researchers produce is field-dependent (which makes this metric unsuitable to compare researchers from different disciplines). For example, some disciplines cite more extensively than others, which artificially increases this metric.

- The h-index also does not take into account the individual’s placement in the author list, which may not be important in some disciplines but it makes the difference in others where the first and last authors have more weight.

- The h-index will never be higher than the total number of papers published, focusing on quantity over quality.

- Moreover, the h-index is an accumulating metric which typically favours senior male researchers as these tend to have published more.

- The h-index has spawned several alternatives (37, as of 2011) in an attempt to counteract these shortcomings. Unfortunately, most of these alternatives are highly correlated with each other, which makes them redundant.

Warnings against the use of these metrics

Many individuals and institutions have warned against the use of these metrics for research assessment, as this has a profound impact on the way research is conducted. Even Nature has signed DORA (which means Springer Nature is against the use of the impact factor for research assessment). The creator of the JIF, Eugene Garfield, also stated that the JIF was not appropriate for research assessment. Even Clarivate Analytics, the company that generates the JIF, stated that “What the Journal Impact Factor is not is a measure of a specific paper, or any kind of proxy or substitute metric that automatically confers standing on an individual or institution that may have published in a given journal.” The creator of the h-index, Jorge Hirsch, warned that the use of h-index as a measurement of scientific achievement could have severe negative consequences.

Consequences

The focus on citations has severe consequences on scientific research, as it creates a research culture that values the quantity of what is achieved rather than the quality. For example, the use of the JIF and h-index results in the tendency for individuals that experienced success in the past will more likely experience success in the future, an effect known as the Matthew effect. High-risk research that is likely to fail or research that only provides interesting results over the long term is discouraged by focusing on the quantity of outputs. The focus on short term successes therefore reduces the likelihood of unexpected discoveries that could be of immense value to scientific research and society.

When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure. – Goodhart’s Law

So what now?

Rather than using metrics to evaluate scientific outputs or researchers, it may be impossible to objectively assess the quality of research, or reach a universal agreement on how to assess research quality. Instead, we could start judging the content of research by reading the scientific article or the research proposal rather than looking at citation metrics. This means that in an increasingly interdisciplinary world researchers will have to communicate their findings or proposals in different ways that are, to a certain extent, understandable to peers in other fields. If that sounds too simplistic, there are also some other great initiatives listed below that serve as alternatives to citation-based metrics in assessing research quality:

Alternative methods and examples of research assessment

- Narrative CV’s allow researchers to focus on a limited number of outputs which they can highlight in more depth, shifting away from quantity towards the content (see for example NWO and UKRI and this webinar evaluating the implementation of the CVs)

- List the contributions per author rather than focusing on the author order (CRediT)

- Time to Say Goodbye to Our Heroes?

- University of Utrecht’s Open Science Programme

- Include mentorship, well-being, diversity and inclusion in assessment (see also the Diversity Approach to Research Evaluation, DARE). For example, reference letters from those supervised or managed could be included in evaluations.

- Use reporting guidelines to increase transparency (see the EQUATOR network)

- The Rigor and Transparency Index Quality Metric for Assessing Biological and Medical Science Methods

- Rethinking Research Assessment: Ideas for Action

- Use broader indicators such as the Academic Careers Understood through MEasurement and Norms (ACUMEN), the Open Science Career Assessment Matrix (OS-CAM), Advancing Research Intelligence Applications (ARIA) or a values-enacted approach such as HuMetricsHSS

- Room for everyone’s talent

- Tools to Advance Research Assessment (TARA)

- Using article metrics, for example: Using the downloads rather than citations as an indicator for use or impact of an article

- Assess and reward teams rather than individual researchers, as research is intrinsically collaborative (see for example NWO Spinoza/Stevin prizes)

- UCL Bibliometrics Policy

See also:

1) Brito and Rodríguez-Navarro 2019, Seglen 1997, Brembs et al. 2013, Callaham et al. 2002, Glänzel and Moed 2002, Rostami-Hodiegan and Tucker 2001, Seglen 1997, and Lozano et al. 2012

2) Caplar et al. 2017, Chakravartty et al. 2018, King et al. 2017, and Macaluso et al. 2016

3 comments